This is a transcript of Arthur Delbridge's 2008 Remembrance Day talk at the Mt Wilson Village Hall, following the service at the War Memorial.

Who are or were the people whose names are engraved on our war memorial? What can we know of them that throws light on how they came to go to war? What did it mean to them and to their families? These are questions that take some probing into the written and printed records that have been left for us and others to read. I am grateful for the access I have had to these records, and grateful too that so many of them have been given to the Historical Society, and so, helping the community to know its own history. For me the Society‘s archives have played a vital role yet again. Particular thanks are due to Mary Reynolds for her tireless work on these records over the last 12 years or more —she is a true historian. Thanks also to John and Helen Cardy who continue to spend many hours regularly maintaining the files and boxes for easy access in the village Study Centre. And my thanks to Florence who keeps me sane, and does the typing and fixing. And today I must thank particularly those members and friends of the Society who, in the case of the two men whose lives we are hearing about today, have helped us understand their stories. In particular I welcome Helen Naylor and members of her family, including Andy Yeates, who has been writing his grandfather‘s history and has allowed me to use it for this talk. Andy has also brought Robert Morley‘s war service medals, including the Military Cross.

William Hilder Gregson

I‘d like to begin by reading from the Roll of Honour, in the Australian War Memorial, Canberra:

Gregson, Sgt William Hilder, 7th Field Coy, Australian Engineers. Killed in action, 14th November 1916, aged 39. Son of Jesse and Catherine Maclean Gregson, husband of Grace Gregson, native of Waratah NSW.

In the library of the Historical Society there is a Gregson family diary of some 150 pages, written by hand, from which we learn that William was born in Newcastle, that his father Jesse had come to New South Wales from England to seek his fortune. Here, among other things he discovered Mt Wilson, through his friends the Merewethers of Dennarque in Church Lane. Jesse Gregson bought a property and developed both house and garden here and from 1880 onwards never missed spending a summer at Yengo, his mountain retreat. 'Yengo,‘ he said, 'was to me and to all the children a place we were always glad to come to and always sorry to leave.‘ He generally came to Yengo with his wife and children early in December each year and remained till early April. In 1870 he had married Katie Maclean. The diary says that the two boys of the family, Willie and Edward, 'amused themselves exploring the adjacent rock country, cutting tracks to favourite places‘.

The boys were sent to school at All Saints College at Bathurst. The mother‘s diary notes that 'both my boys owe almost everything of their reverence for all that is good to the teaching they received and the example they saw at All Saints‘. Both in turn served as head boys at this school and went on to Sydney University and 'in due course‘ graduated. Willie, Bachelor of Arts in 1898, Bachelor of Engineering in 1901 and, Edward, Bachelor of Arts in 1903.

Over the years the family travelled quite extensively around the world. While they were in America, Willie went off to find work in Canada as a draughtsman. He and his brother continued to travel widely—Italy, Switzerland, the Rhine area, France and eventually England. In 1912 Willie married, and a daughter was born in June 1914. Meanwhile he had gained professional qualifications as a licensed surveyor, working mainly with mining companies. At the outbreak of war he joined a rifle club and before long enlisted for military service, serving in the 7th Field Engineering Company. Three months later he had gained two stripes as a Corporal, and his unit sailed from Sydney for the Great War beyond. The 7th Engineers took up foreign duties first at the Suez Canal and from there in March 1916 to France. The Unit was soon directly engaged in the great, long and terrible Battle of the Somme. In all the literature of war that name strikes dread—for all the carnage, ineptitude and sheer waste of life. (In which for the British Army alone, there were 150,000 men killed. The very first day of this battle, 1st July 1916, saw the death of 20,000 British soldiers.)

Siegfried Sassoon

The General

"GOOD MORNING; good-morning!” the General said

When we met him last week on our way to the Line.

Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of „em dead,

And we?re cursing his staff for incompetent swine.

“He?s a cheery old card,” grunted Harry to Jack

As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack

. . . . . . . .

But he did for them both by his plan of attack.

From this point Willie‘s military record becomes sparse and uncertain. It is clear that he was wounded in action in November 1916, but his casualty report is filled with uncertainties:

- 18th November, 1916: Wounded in action.

- 27th February, 1917: Now reported wounded and MISSING.

- 3rd August, 1917: Previously reported wounded and missing, and now reported killed in action.

That‘s the official record, but the family diary gives more detail. 'On the Somme, six months passed over, but on 14th November 1916 he was reported 'wounded' during an attack on Le Sars – from that time he was lost sight of, and though every possible enquiry and search was made for him, both from here and by relatives in England, nothing more was ever heard of his state. A year later his grave was found and reported by the military authorities, AND HIS IDENTITY DISCS RETURNED TO HIS WIDOW‘.

This is the direct account from the family diary, but their undoubted grief is not expressed or mentioned. Not a word on the hopeless difficulty of realising what had happened, of achieving some sort of acceptance of the bare announcement of his death. No 'closure‘. That‘s a rather fashionable word for an old idea meaning some final acceptance of a long felt loss. But the diary contains no expression of the family‘s grief that Willie is gone. It‘s beyond words.

What I find most touching about this story is that Willie‘s decision to enlist must have been so hard to reach. It is not like the stories of young fellas, enlisting for the adventure of it, or getting away from the hum drum of life in an office or on the farm. We hear such stories, but here was William in his mid-thirties, married, with a young daughter, doing useful work, yet volunteering for army service, doing his duty for his country. And then missing and dead at age 39, and his widow left with his identity discs; facing post-war life in a country impoverished by the war, and with his name now on our war memorial.

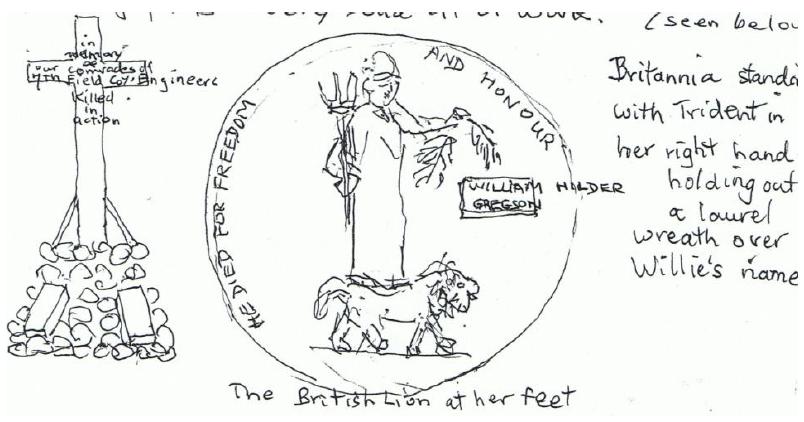

Only a small photograph of Willie could be located, but Meg Fromel (Gregson) did find some notes and sketches tucked inside one of her father’s diaries. Her father, Edward Jesse Gregson, had also served in the First World War and, at some later time, found his son Willie’s grave and his name on a memorial in France and drew a sketch of the memorial (the skect is shown below) and a map of the location. His notes say:

Memorial to our fallen comrades, erected at Tara Hill, between Pozieres and Albert, Somme. The cross and base is made from oak and stone taken from the ruins of a church at Martinpuich & inserted in base are four wooden tablets on one of which your brother’s name is inscribed. The design is by Lieut. Cartwright MC, 7th Coy. & was erected by the boys of the Coy. The memorial stands about 12 ft high and is a very solid bit of work.

Britannia standing with trident in her right hand holding out a laurel wreath over Willie’s name.

The British Lion at her feet.

Ronald Morley MC

The other name I chose from the war memorial for today‘s presentation was Ronald Morley whose name is accompanied by the letters MC for Military Cross. I soon discovered that a life of Ronald Morley is now being written by his grandson Andy Yeates who is here with us for this commemoration today. He has kindly sent me a draft copy of his work in progress. Andy is writing a very full and fascinating account of his grandfather‘s life, including the long and arduous time in the Great War. Naturally I suggested that he might like to give the paper today but he asked me to carry on with it and it is with great pleasure that I make constant use of his knowledge about Ronald Morley, not only for his time as a soldier but also the time that he spent very happily in Mt Irvine and Mt Wilson.

Ronald Morley‘s brother Harold, older by ten years, was one of the three original pioneers who came to Mt Irvine with two friends, Charles Scrivener and Basil Knight Brown, in 1897 after graduating from Hawkesbury Agricultural College. Charles Scrivener senior had surveyed a way to Mt Irvine from Bilpin and the three young men walked across this infamous gully to take up three parcels of land and begin the settlement that is now such an important and beautiful part of our community.

Andy writes that as a schoolboy, through his teenage years and into his twenties Ronald spend many happy times at Irvineholme with his brother. 'Days were filled with hard work on the farm and shooting, bush walks, horse riding and tennis. In the evenings Harold and Ronald talked and laughed and sang favourite songs. The two brothers were strong and fit and photos show them as exceptionally striking young men. Ronald revelled in the Mt Irvine and Mt Wilson community and social life. He was well known in homes in the district and it is said that he loved to turn any occasion into a bit of a party.‘

There is a connection too with the Gregson family. On one occasion when passing through Mt Wilson, Ronald became seriously ill and the Gregson family insisted that he should stay at their home to be looked after. It turned out that he was suffering from pneumonia and he spent weeks in Mt Wilson, and then back at Irvineholme being nursed back to health. Harold Morley was convinced that his younger brother‘s life was saved by the kindness of the Gregsons and the doctors whom they brought in to Mt Wilson to attend him.

Ronald enlisted in 1915 in the 4th Battalion which was shipped to Alexandria for basic training. While here he met by chance Pedder Scrivener, brother of Charles Scrivener of Mt Irvine. These two met again in 1918, and in their letters home both men spoke about being overjoyed and emotional at so unexpectedly finding a familiar face.

Sent to Gallipoli in November 1915, some time after the famous landing, Ronald thankfully survived, and the Battalion returned to Alexandria before seeing action again in France. For most of 1916 and into 1917 Ronald‘s Unit continued fighting in France. It was a long period of unbroken war service. Early in 1917 he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant before being sent to England for training as an instructor in the handling of deadly gas. Ronald was then made a full Lieutenant and in February 1918 he rejoined his Battalion in France.

Within months he became involved in an operation for which he was later decorated with the Military Cross. From this point I have taken up the story from Andy‘s book about his grandfather‘s life.

A significant component of the Australian strategy was the use of small raiding parties which would carry out raids into and behind enemy lines. Generally the raiding parties consisted of one officer accompanied by around four to six other soldiers (or 'ranks‘ as they were known at the time). These raids were highly dangerous to the parties carrying them out and as a result the standard modus operandi was for the raids to be carried out under cover of darkness.

It was decided to extend the raids to include daylight raids. Enter one Lieutenant Ronald Morley who on 5th July 1918 had re-joined his battalion at the front line from field hospital. The daylight raids were to follow a similar methodology as the night raids. However the significantly increased risks of such stealth sorties without cover of darkness would have been well recognised.

The area near Strazeele where the raid took place was open farm country, gently undulating and with some hedges and trees. Visibility in the area was excellent. We know this from Peder Scrivener‘s firsthand account of the action, which Peder observed from an artillery viewing platform at some distance from where the action took place. (Isn‘t it remarkable that these two young fellas from Mt Irvine would find each other twice in this war.)

In the middle of a summer‘s day on 11th July 1918 Lieutenant Ronald Morley and four other ranks left their lines and moved towards the German lines at a distance of some 200 metres using the cover of hedges and ditches. As Ronald set out on the mission, he would have been acutely aware that if he or his comrades were seen, they would most certainly have been cut to pieces by German machine guns which were positioned to their front.

According to Ronald‘s account, the Germans did not have a sentry posted, and they were sleeping in the warmth of the summer‘s day. As a result of these factors and the skills and daring of Ronald and his men, they were able to storm and surprise a trench and take prisoners without disturbing German troops nearby.

At this point, the raid had already been an outstanding success and the group would have been well justified in returning to their lines with their prisoners. However Ronald decided to take advantage of their situation. He told one of his men (he only had four!) to take the captured prisoners back to the Australian lines. The balance of the raiding party proceeded to the next trench. Here the Germans were also taken by surprise however they did fire on the Australians at close range and, according to Ronald‘s account, the Australians had to 'get busy‘ with hand grenades which forced the Germans to quickly surrender.

The outcome of the raid was that without an Australian casualty, the five Australian soldiers captured thirty one prisoners, took four German machine gun positions and enabled the Australian line to be advanced by 250 yards. All of this in broad daylight against the Prussian Guard: elite soldiers who were the pride of the German military.

Later on 22nd July the Major-General commanding Ronald‘s Division approved the award of the Military Cross for 'conspicuous gallantry and leadership‘.

After the war in early 1919 Ronald was in England as part of military decampment and in accordance with an invitation received from the Lord Chamberlain, he attended Buckingham Palace on the morning of Saturday 29th March to receive his Military Cross decoration from King George V.