Remembrance Day

Early History of Mt Wilson, Mt Irvine and Bell War Memorial

- Details

The War Memorial photographed c 1919

To appreciate the full significance of this simple, uncluttered memorial one has to understand the communities who joined together to create it. In the primary documents of 1919 it is referred to as ‘The Mt Wilson and Mt Irvine and Bell Soldiers’ Memorial’. Scanning the names carved on the granite of the Memorial that should not be any surprise to those who know a little of the past of this district.

The construction of a memorial to those who served in World War 1 or ‘The Great War’ should be seen against the impact, sometimes disturbing, that war had on even small isolated communities such as Bell, Mt Irvine and Mt Wilson. It is sufficient to observe the number of names listed to appreciate the extent of the involvement of these tiny communities. Their coming together to fulfill their combined desire to honour those who served is a tribute to their sense of belonging in spite of the distances and the state of roads which had to be traversed. Reading accounts in the Lithgow Mercury printed during these war years of social gatherings, many being held in the local school, one senses pleasure, friendship and dependability amongst those who lived and worked in these communities.

The written evidence for this story commences in 1919, in documents given to the Society by the Valder family. It is clear that Miss Helen Gregson, a daughter of Jesse Gregson, the founder of “ Yengo” Mt Wilson played an important role in setting up ‘The Mt Wilson, Mt Irvine and Bell Soldiers’ Memorial Committee’. She became its first Secretary. The loss of one of her two brothers, Willie, in 1916, must have influenced her strongly. Her father, devastated by the loss of his son, also played an influential role behind the scenes, frequently being consulted by Helen.

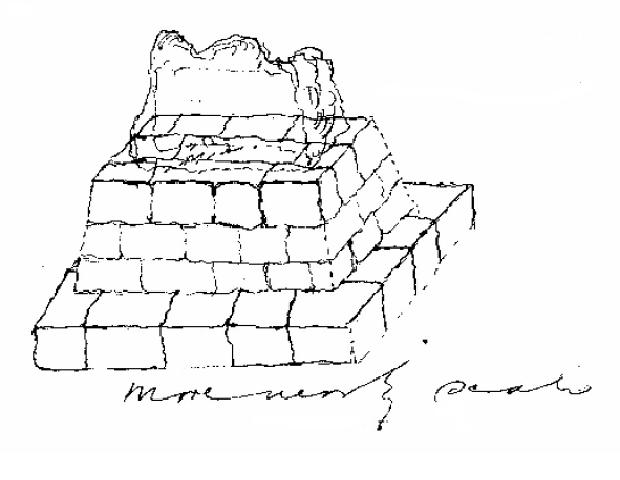

Charles Robert Scrivener, already distinguished in the field of surveying, having been the first Commonwealth appointed Director of Lands & Surveys, had retired to Mt Irvine in 1915. Here he built ‘Taihoa’, a quite unique home, and operated a timber mill. He was well established in the committee by 1919, representing Mt Irvine. He also had sons who served in the War. The Hall family from Bell throughout the period of the construction of the Memorial was also actively involved. One of their sons W. [Bill] Hall had paid the supreme sacrifice. According to the correspondence records the committee was operating fully by early 1919. Subscriptions from members of the communities were being received; diagrams and sketches of the proposed memorial, drawn by Charles R. Scrivener, were in evidence attached to letters. And there was much debate over the decision to order the vital granite block on which the names were to be inscribed.

Where was the memorial to be built? A delightful piece of evidence is a letter written on 16th March 1919 by Mrs Flora Helena Mann of ‘Dennarque’ in which she states: “Relative to the erection of a Roll of Honour to those soldiers who enlisted from Bell, & Mt Wilson & Mt Irvine, I shall be pleased to give a part of Portion 26 - Parish of Irvine, the County of Cook ----- as a site for the purposes. Your Committee is at liberty to enter on this area & do necessary work in connection with the memorial provided that a new fence is properly erected on the new boundary line.------When a survey has been made of the small area on sketch I shall be quite prepared to transfer that area to the Committee or to any persons who may be appointed as trustees for the area.” Signed Flora H. Mann. While her elder daughter, Esmey Burfitt, was to become a trustee for the memorial, contrary to what has been stated and written elsewhere, it was her mother who originally offered the gift of the land as she was owner of the property in 1919. Flora Mann died in 1921. She had three sons serving in World War 1, one of whom, Alfred, was killed.

This grant of land was not officially transferred to the Committee until 21st October 1924, being from the Estate of Flora H. Mann {E M E Burfitt, E G A Moran, J & F Mann & A W M d’Apice} an area of 13 ¾ Perches, part of Portion 26, Parish of Irvine, County of Cook -- to Helen Gregson, Albert Kirk, Esmey Burfitt {Joint Tenancy}.

A significant feature of this grant is that an owner of land had graciously and generously given this part for a special collective community purpose. It is a theme of this community’s history as one explores its past and finds many similar examples.

The decision to purchase the granite block was made finally in May 1919 by Charles R Scrivener. He wrote to Helen Gregson telling her that he had written to W.G. Partridge of Sydney and a price of 54 pounds had been quoted which was to include the lettering, punctuation, and all other marks on the granite, 352 in number.

The basalt foundation stones were to be brought from Taihoa Creek Mt Irvine by horse team with C P Scrivener [Charley], a son of Charles Robert. Sam and Ellis Hall of Bell constructed the foundations and the surrounds of the simple monument.

In 1993 Tom Kirk wrote a short account of the building of this memorial in which he gave proper emphasis to those who carried out the hard physical work, without whom nothing could have been achieved. Just as little can be gained without those prepared to work, so it is that the workers must be paid and the materials they use paid for. The vital role of the Soldiers’ Memorial Committee was to raise funds.

Who were the subscribers to this Joint Community Memorial? In the archives are absorbing documents written by those involved at the time, revealing not only the diversity of those contributing but the size of the gift and on the other side of the ledger, the costs of wages and materials. In June 1919 there was to be a rather serious shortfall in the funds, but Charles Robert was not at all deterred and suggested to Helen Gregson a short list of subscribers on whom the Committee could rely for further help. His confidence in those on that short list (which included himself) was not misplaced.

Below is a list of the Subscribers as finally drawn up in 1923. By that time some had passed on, including Charles Robert Scrivener. An * next to a name indicates that person had died by 1923. [We have also added the name of the district with which the persons listed were associated, where we are sure.] Lists of this type are invaluable when conducting local history research.

| Subscriber | District |

|---|---|

| * Charles R Scrivener | Mt Wilson |

| Dr W. Burfitt | Mt Wilson |

| * E E Brown | Mt Wilson |

| George Valder | Mt Wilson [Peter Valder's grandfather] |

| Jesse Gregson | Mt Wilson |

| Ivie J Sloan | Mt Wilson |

| Reginald Clark | Mt Wilson |

| Phil Forrest | Mt Wilson [a photographer of some standing; he took some wonderful photos in Mt Wilson at that time |

| Mrs Willie Gregson | Mt Wilson |

| Miss Helen Gregson | Mt Wilson |

| Miss Bessie Gregson | Mt Wilson |

| Mr F Morley | Mt Irvine |

| * Mr Sydney Kirk | Mt Wilson |

| James Nisbett | Friend of Gregsons |

| Captain Tuson | Unsure |

| Mrs Eva Moran [nee Mann] | Mt Wilson |

| Professor M. MacCallum | Friend of Gregsons |

| Mr J Anderson | Mt Irvine & Bilpin |

| Mr J Joshua | Mt Wilson 'Campanella' |

| Albert Kirk | Mt Wilson |

| Mr Bunting | Mt Wilson |

| Mrs Connors | Mt Wilson - caretaker 'Bebeah' |

| W.L. King | Mt Irvine 'Touri' |

| Mr Sam Hall | Bell |

| J. Knight-Brown | Mt Irvine |

| Basil Knight-Brown | Mt Irvine |

| Norman Knight-Brown | Mt Irvine |

| Harold B Morley | Mt Irvine |

| Charles R Scrivener | Mt Irvine |

| A.M. Walsh | Mt Irvine |

| J.O. Rourke | Bell |

| * J Hartley | Caretaker at 'Yarrawa' |

| * Mrs Sharp | Post Mistress at 'Beowang' for 20 years + |

| Mrs Alethea Shaw | Post Mistress 1919 at 'Beowang' ['Withycombe'] |

These subscribers raised over 102 Pounds, a substantial sum for those times.

Throughout 1919 the work continued as each stage of the construction was completed. A large block of granite from the Gunning district was transferred by horse teams from Mt Victoria railway station to the memorial site, where a large tripod of poles was used to place it correctly in position.

While it is not practicable here to provide comprehensive details of costs, it is enlightening to record one or two examples. For example a certain George Donald supervised the granite being put in place. He came in March from Sydney to inspect the basalt foundation and for this service he charged 2 pounds 7 shillings. Ellis Hall of Bell worked 107 hours at 15pence per hour from March 17th to April 2nd; the charge for one horse drawing logs was 14 shillings and the haulage of 12 loads of stone at 4 shillings a load. These figures reflect a very different pace of life, the limited technology and the demands on physical strength in those times. In all the final costs came close to 90 pounds, with some additional work in 1924 on the lettering on the memorial, costing 9 pounds.

It is a pity there are no written records of the official unveiling ceremony held on 29th November 1919 but there is a written statement by Miss Helen Gregson which tells its own story.

Mount Wilson, Mount Irvine & Bell Soldiers Memorial

“Owing to bad weather having prevented the attendance of many who would otherwise have been present on the occasion of the ‘Unveiling of the Soldiers’ Memorial’ at Mount Wilson on 29th November last business was postponed on that occasion.—The Committee now beg to call a Special Meeting of Subscribers for Saturday 20th December at 3.p.m. to consider the advisability of placing a namestone alongside the tree planted to the memory of W. H. Gregson, near the Soldiers Memorial.

As only a personal vote will carry weight the Committee hope that all those interested will make a point of attending in order to express their opinion on the matter.” Signed Helen Gregson, Secretary, ‘Yengo’ Mt Wilson 14th December 1919.

Today that small stone pillar, carrying the letters W.H.G. 1877-1916 still stands to the right of the Memorial. Its presence answers the query as to how those people voted in 1919 when they met in the School House on 20th December. This small structure was desired by the Gregson family to remember Willie Gregson. Nevertheless there was some difference of opinion best expressed by Charles R Scrivener in a letter to Miss Gregson at the time; he said: “The public memorial is ample, its purpose to indicate the public appreciation of the patriotism & courage of the men whose names are recorded-------“ he stressed the importance of it to the coming generation. His final comment was “The memorial is a place of pride and has nothing to do with sorrow”.

It seems fitting to close this brief early history with that sentiment.

It is of interest to mention some developments which could be elaborated on more fully in further research on the Memorial.

There is reference to a tree planted for Willie Gregson — a Deodar. In fact 3 trees were planted for the 3 men from this district who were killed in that War, and as a background to the Memorial members of the Mann family each planted a tree in the area behind the Memorial in Dennarque. Many years later in about 1952 the then owner of Dennarque, Sir John Austin, donated the land on which these trees were planted to the Memorial Reserve.

In December 1919 Charles R Scrivener was already questioning the wisdom of having Trustees. He proposed transferring the care and responsibility for the Memorial and its land to the then Blue Mountains Shire Council at Lawson, who did agree to undertake this task. However by 1923 Charles R. Scrivener had already resigned as a Trustee and his place had been taken by Albert Kirk. Helen Gregson and Esmey Burfitt were the other two Trustees. Charles R. Scrivener now in poor health was to die later in 1923. He was a great loss to both communities. The debate concerning whether the Blue Mountains Shire Council should be involved continued in that year and was finally decided by a vote of subscribers strongly in favour of keeping control in the hands of the Trustees for the local Community. At the time Helen Gregson invited Harold Morley and Basil Knight-Brown from Mt Irvine to join the three approved Trustees from Mt Wilson. They declined on the basis of problems attending meetings and work commitments. Later the Memorial came under the care of the Mt Wilson Sights Reserve Trust, until 1989 when the Blue Mountains City Council undertook the responsibility.

Bibliography:

Correspondence from the Mt Wilson, Mt Irvine & Bell

Soldiers Memorial Committee 1919-1923. Also Financial Records from that same Committee.

Tom Kirk’s Paper, March 1993

Articles in the Lithgow Mercury 1911-1912, 1914, 1916.

Australian Archives- Bell / Mt Wilson Postal records.

‘Mt Irvine a History’ [Mt Irvine Progress Assoc.]

Notes and details of land transfer from Michael Mann, a grandson of Flora Mann and a nephew of Esmey Burfitt.

The Photograph of the War Memorial came from the Shaw Collection in the Photographic Archives of the Mt Wilson & Mt Irvine Historical Society. The Shaw family lived at ‘Beowang’ c. 1918-c.1921. Mrs Shaw was the Post Mistress when the Post Office was in a small cottage in ‘Beowang’ [now known as ‘Withycombe’].

This brief history is produced by the Mt Wilson & Mt Irvine Historical Society Inc., November 11th 2002. Revised 2004.

Sketch of the War Memorial - Taken from correspondence from Charles R Scrivener, the Mt Irvine representative on the Soldiers Memorial Committee in 1919.

-

LEST WE FORGET IN HONOUR OF MANN JEF MC * GREGSON WH KIRK SWG GREGSON EJ HALL E VALDER G WYNNE RO DSO * HALL W JOSHUA JM SCRIVENER P P MC HATSWELL EEC SHARP FJ TUSON H GEARY J TUSON AG MORLEY CR MC KIRK HCL NIXON FJ * MANN ATO KIRK VCL CLARK RG MANN F F O’ROURKE TJ CLARK LS SCRIVENER TM BUSBY JB McDONALD JP SOLDIERS WHO SERVED KING & COUNTRY *KILLED 1914 - 1918 1939 - 1945 GUNN M * KNIGHT BROWN NH LE MESURIER L SMITH C KNIGHT BROWN PJ CLARKE CR KIRK SBW MOTTESHEAD G WYNNE MC VIETNAM: GUNN KR

2008 Remembrance Day Transcript

- Details

This is a transcript of Arthur Delbridge's 2008 Remembrance Day talk at the Mt Wilson Village Hall, following the service at the War Memorial.

Who are or were the people whose names are engraved on our war memorial? What can we know of them that throws light on how they came to go to war? What did it mean to them and to their families? These are questions that take some probing into the written and printed records that have been left for us and others to read. I am grateful for the access I have had to these records, and grateful too that so many of them have been given to the Historical Society, and so, helping the community to know its own history. For me the Society‘s archives have played a vital role yet again. Particular thanks are due to Mary Reynolds for her tireless work on these records over the last 12 years or more —she is a true historian. Thanks also to John and Helen Cardy who continue to spend many hours regularly maintaining the files and boxes for easy access in the village Study Centre. And my thanks to Florence who keeps me sane, and does the typing and fixing. And today I must thank particularly those members and friends of the Society who, in the case of the two men whose lives we are hearing about today, have helped us understand their stories. In particular I welcome Helen Naylor and members of her family, including Andy Yeates, who has been writing his grandfather‘s history and has allowed me to use it for this talk. Andy has also brought Robert Morley‘s war service medals, including the Military Cross.

William Hilder Gregson

I‘d like to begin by reading from the Roll of Honour, in the Australian War Memorial, Canberra:

Gregson, Sgt William Hilder, 7th Field Coy, Australian Engineers. Killed in action, 14th November 1916, aged 39. Son of Jesse and Catherine Maclean Gregson, husband of Grace Gregson, native of Waratah NSW.

In the library of the Historical Society there is a Gregson family diary of some 150 pages, written by hand, from which we learn that William was born in Newcastle, that his father Jesse had come to New South Wales from England to seek his fortune. Here, among other things he discovered Mt Wilson, through his friends the Merewethers of Dennarque in Church Lane. Jesse Gregson bought a property and developed both house and garden here and from 1880 onwards never missed spending a summer at Yengo, his mountain retreat. 'Yengo,‘ he said, 'was to me and to all the children a place we were always glad to come to and always sorry to leave.‘ He generally came to Yengo with his wife and children early in December each year and remained till early April. In 1870 he had married Katie Maclean. The diary says that the two boys of the family, Willie and Edward, 'amused themselves exploring the adjacent rock country, cutting tracks to favourite places‘.

The boys were sent to school at All Saints College at Bathurst. The mother‘s diary notes that 'both my boys owe almost everything of their reverence for all that is good to the teaching they received and the example they saw at All Saints‘. Both in turn served as head boys at this school and went on to Sydney University and 'in due course‘ graduated. Willie, Bachelor of Arts in 1898, Bachelor of Engineering in 1901 and, Edward, Bachelor of Arts in 1903.

Over the years the family travelled quite extensively around the world. While they were in America, Willie went off to find work in Canada as a draughtsman. He and his brother continued to travel widely—Italy, Switzerland, the Rhine area, France and eventually England. In 1912 Willie married, and a daughter was born in June 1914. Meanwhile he had gained professional qualifications as a licensed surveyor, working mainly with mining companies. At the outbreak of war he joined a rifle club and before long enlisted for military service, serving in the 7th Field Engineering Company. Three months later he had gained two stripes as a Corporal, and his unit sailed from Sydney for the Great War beyond. The 7th Engineers took up foreign duties first at the Suez Canal and from there in March 1916 to France. The Unit was soon directly engaged in the great, long and terrible Battle of the Somme. In all the literature of war that name strikes dread—for all the carnage, ineptitude and sheer waste of life. (In which for the British Army alone, there were 150,000 men killed. The very first day of this battle, 1st July 1916, saw the death of 20,000 British soldiers.)

Siegfried Sassoon

The General

"GOOD MORNING; good-morning!” the General said

When we met him last week on our way to the Line.

Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of „em dead,

And we?re cursing his staff for incompetent swine.

“He?s a cheery old card,” grunted Harry to Jack

As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack

. . . . . . . .

But he did for them both by his plan of attack.

From this point Willie‘s military record becomes sparse and uncertain. It is clear that he was wounded in action in November 1916, but his casualty report is filled with uncertainties:

- 18th November, 1916: Wounded in action.

- 27th February, 1917: Now reported wounded and MISSING.

- 3rd August, 1917: Previously reported wounded and missing, and now reported killed in action.

That‘s the official record, but the family diary gives more detail. 'On the Somme, six months passed over, but on 14th November 1916 he was reported 'wounded' during an attack on Le Sars – from that time he was lost sight of, and though every possible enquiry and search was made for him, both from here and by relatives in England, nothing more was ever heard of his state. A year later his grave was found and reported by the military authorities, AND HIS IDENTITY DISCS RETURNED TO HIS WIDOW‘.

This is the direct account from the family diary, but their undoubted grief is not expressed or mentioned. Not a word on the hopeless difficulty of realising what had happened, of achieving some sort of acceptance of the bare announcement of his death. No 'closure‘. That‘s a rather fashionable word for an old idea meaning some final acceptance of a long felt loss. But the diary contains no expression of the family‘s grief that Willie is gone. It‘s beyond words.

What I find most touching about this story is that Willie‘s decision to enlist must have been so hard to reach. It is not like the stories of young fellas, enlisting for the adventure of it, or getting away from the hum drum of life in an office or on the farm. We hear such stories, but here was William in his mid-thirties, married, with a young daughter, doing useful work, yet volunteering for army service, doing his duty for his country. And then missing and dead at age 39, and his widow left with his identity discs; facing post-war life in a country impoverished by the war, and with his name now on our war memorial.

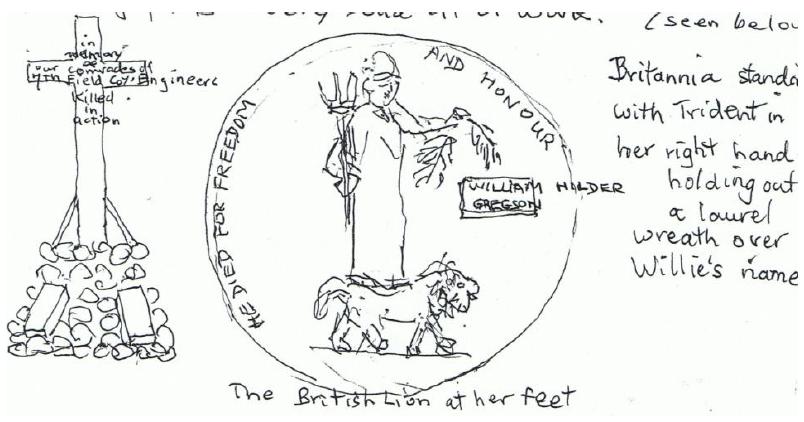

Only a small photograph of Willie could be located, but Meg Fromel (Gregson) did find some notes and sketches tucked inside one of her father’s diaries. Her father, Edward Jesse Gregson, had also served in the First World War and, at some later time, found his son Willie’s grave and his name on a memorial in France and drew a sketch of the memorial (the skect is shown below) and a map of the location. His notes say:

Memorial to our fallen comrades, erected at Tara Hill, between Pozieres and Albert, Somme. The cross and base is made from oak and stone taken from the ruins of a church at Martinpuich & inserted in base are four wooden tablets on one of which your brother’s name is inscribed. The design is by Lieut. Cartwright MC, 7th Coy. & was erected by the boys of the Coy. The memorial stands about 12 ft high and is a very solid bit of work.

Britannia standing with trident in her right hand holding out a laurel wreath over Willie’s name.

The British Lion at her feet.

Ronald Morley MC

The other name I chose from the war memorial for today‘s presentation was Ronald Morley whose name is accompanied by the letters MC for Military Cross. I soon discovered that a life of Ronald Morley is now being written by his grandson Andy Yeates who is here with us for this commemoration today. He has kindly sent me a draft copy of his work in progress. Andy is writing a very full and fascinating account of his grandfather‘s life, including the long and arduous time in the Great War. Naturally I suggested that he might like to give the paper today but he asked me to carry on with it and it is with great pleasure that I make constant use of his knowledge about Ronald Morley, not only for his time as a soldier but also the time that he spent very happily in Mt Irvine and Mt Wilson.

Ronald Morley‘s brother Harold, older by ten years, was one of the three original pioneers who came to Mt Irvine with two friends, Charles Scrivener and Basil Knight Brown, in 1897 after graduating from Hawkesbury Agricultural College. Charles Scrivener senior had surveyed a way to Mt Irvine from Bilpin and the three young men walked across this infamous gully to take up three parcels of land and begin the settlement that is now such an important and beautiful part of our community.

Andy writes that as a schoolboy, through his teenage years and into his twenties Ronald spend many happy times at Irvineholme with his brother. 'Days were filled with hard work on the farm and shooting, bush walks, horse riding and tennis. In the evenings Harold and Ronald talked and laughed and sang favourite songs. The two brothers were strong and fit and photos show them as exceptionally striking young men. Ronald revelled in the Mt Irvine and Mt Wilson community and social life. He was well known in homes in the district and it is said that he loved to turn any occasion into a bit of a party.‘

There is a connection too with the Gregson family. On one occasion when passing through Mt Wilson, Ronald became seriously ill and the Gregson family insisted that he should stay at their home to be looked after. It turned out that he was suffering from pneumonia and he spent weeks in Mt Wilson, and then back at Irvineholme being nursed back to health. Harold Morley was convinced that his younger brother‘s life was saved by the kindness of the Gregsons and the doctors whom they brought in to Mt Wilson to attend him.

Ronald enlisted in 1915 in the 4th Battalion which was shipped to Alexandria for basic training. While here he met by chance Pedder Scrivener, brother of Charles Scrivener of Mt Irvine. These two met again in 1918, and in their letters home both men spoke about being overjoyed and emotional at so unexpectedly finding a familiar face.

Sent to Gallipoli in November 1915, some time after the famous landing, Ronald thankfully survived, and the Battalion returned to Alexandria before seeing action again in France. For most of 1916 and into 1917 Ronald‘s Unit continued fighting in France. It was a long period of unbroken war service. Early in 1917 he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant before being sent to England for training as an instructor in the handling of deadly gas. Ronald was then made a full Lieutenant and in February 1918 he rejoined his Battalion in France.

Within months he became involved in an operation for which he was later decorated with the Military Cross. From this point I have taken up the story from Andy‘s book about his grandfather‘s life.

A significant component of the Australian strategy was the use of small raiding parties which would carry out raids into and behind enemy lines. Generally the raiding parties consisted of one officer accompanied by around four to six other soldiers (or 'ranks‘ as they were known at the time). These raids were highly dangerous to the parties carrying them out and as a result the standard modus operandi was for the raids to be carried out under cover of darkness.

It was decided to extend the raids to include daylight raids. Enter one Lieutenant Ronald Morley who on 5th July 1918 had re-joined his battalion at the front line from field hospital. The daylight raids were to follow a similar methodology as the night raids. However the significantly increased risks of such stealth sorties without cover of darkness would have been well recognised.

The area near Strazeele where the raid took place was open farm country, gently undulating and with some hedges and trees. Visibility in the area was excellent. We know this from Peder Scrivener‘s firsthand account of the action, which Peder observed from an artillery viewing platform at some distance from where the action took place. (Isn‘t it remarkable that these two young fellas from Mt Irvine would find each other twice in this war.)

In the middle of a summer‘s day on 11th July 1918 Lieutenant Ronald Morley and four other ranks left their lines and moved towards the German lines at a distance of some 200 metres using the cover of hedges and ditches. As Ronald set out on the mission, he would have been acutely aware that if he or his comrades were seen, they would most certainly have been cut to pieces by German machine guns which were positioned to their front.

According to Ronald‘s account, the Germans did not have a sentry posted, and they were sleeping in the warmth of the summer‘s day. As a result of these factors and the skills and daring of Ronald and his men, they were able to storm and surprise a trench and take prisoners without disturbing German troops nearby.

At this point, the raid had already been an outstanding success and the group would have been well justified in returning to their lines with their prisoners. However Ronald decided to take advantage of their situation. He told one of his men (he only had four!) to take the captured prisoners back to the Australian lines. The balance of the raiding party proceeded to the next trench. Here the Germans were also taken by surprise however they did fire on the Australians at close range and, according to Ronald‘s account, the Australians had to 'get busy‘ with hand grenades which forced the Germans to quickly surrender.

The outcome of the raid was that without an Australian casualty, the five Australian soldiers captured thirty one prisoners, took four German machine gun positions and enabled the Australian line to be advanced by 250 yards. All of this in broad daylight against the Prussian Guard: elite soldiers who were the pride of the German military.

Later on 22nd July the Major-General commanding Ronald‘s Division approved the award of the Military Cross for 'conspicuous gallantry and leadership‘.

After the war in early 1919 Ronald was in England as part of military decampment and in accordance with an invitation received from the Lord Chamberlain, he attended Buckingham Palace on the morning of Saturday 29th March to receive his Military Cross decoration from King George V.

2006 Remembrance Day Transcript

- Details

This is a transcript of Arthur Delbridge's 2006 Remembrance Day talk at the Mt Wilson Village Hall, following the service at the War Memorial.

Today is the day for memories, memories centred on our community War Memorial. Australia has two such official days each year; this, sometimes called Armistice Day, and Anzac Day, but they are rather different in emphasis. What is memorialised today is the closing moments of what for a long time we called the 'Great War', the war which came to an end (except in its consequences) at the 11th minute of the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918. We're inclined these days to call it World War I, though the hope had been that it was the war to end all wars.

No such luck!

World War II followed only 20-odd years later. This morning we have heard the call to remember by standing in silence at the 11th minute of the 11th hour. None of us here are likely to have any direct memory of that particular day. Instead we remember different wars – World War II, Korea, Vietnam and now Iraq. The day for each of us is a personal possession related to home, family, neighbourhood – individual memories.

I was still a student at Sydney University in 1939 on the day it was announced on the radio that we were at war with Germany. I still remember the shudder of dread and excitement at hearing the pipe band of the University Regiment suddenly called on parade to march noisily around the University playing patriotic songs, as if to say 'look: we're ready'

Each of us now have strongly personalised memories, whether in grief with the loss of loved ones or with joy at their survival and their safe return. How sobering it is that the saddest cost of World War I to Australia was 60,000 war dead, their graves in distant lands.

Usually I take two names from our War Memorial and try to give a brief account of the lives of the two soldiers, but today a slight variation. I'll talk first about the whole family of Leslie Southee Clark, a family well represented in the village by his daughter Noellie MacLean, born Noellie Clark, and her son Mike. Thinking for a moment about Mike makes me recall the way we lived here in Mt Wilson in the 1970s when Mike and my son Nick were young fellows in their early 20s. You had to go to the post office each day to pick up your mail. If you wanted to make a telephone call, you had to go through the manual switchboard to be put through by the post mistress. I remember once trying to phone my son Nick from Sydney, asking the Post Mistress Val Bailey to put me through to him. And her reply: 'well yes, but he may not be there. He and Mike were going to do some fencing today at Mt Irvine'. That's how close we all were to each other in those days.

The Clark Family

Noellie tells me that in the wider Clark family extended by marriage there were, all told, 14 enlistments into the services of WWI and WWII, but today I'll take just four of them: Noellie's father and her uncle in WWI and her brother and her husband in WWII. Of the four, three survived. Leslie Southee Clark, Noellie's father, was a very successful farmer in Dubbo. He had graduated from Hawkesbury Agricultural College in 1912, returning to Dubbo to develop a notable farming property, to marry and to build a grand Edwardian homestead called Dulcidene. Les Clark had four children, one of whom was Noellie, and another John Byron Marcus Clark who will come into the story again later.

Well, in 1917 Les Clark and his older brother Roland Cuthbert Clark enlisted in the army and were posted as Mechanical Transport Reinforcements. They embarked on HMAT Runic to serve in France, in Les's case as a driver in a military motor transport unit. I've seen a small photograph of Les Clark standing in front of the great lumbering truck he drove, no doubt carrying supplies, ammunition, food and so on up to the front line; an exposed and dangerous occupation. In the photo he looks like a really big man, but Noellie tells us that he was wearing three greatcoats all at once, so cold and snowy was it there. He was demobilised in November 1919 and, returning to his Dubbo property, again became a leading citizen. For 26 years he was President of the Dubbo Show, Vice-President of the Royal Agricultural Society of NSW, he sat on the District Land Board, was Chairman of the Dubbo Hospital and, 'having served in a Transport Company in France, he was honoured to be a Patron of the Dubbo RSL'.

He left Dubbo in 1954 to spend the last 20 years of his life in Mt Wilson at Sefton Hall. This house had originally been built by his father Henry Marcus Clark, the then well-known entrepreneur and retailer who developed a chain of shops, known as Marcus Clarks, in Sydney and country NSW. Some of us would remember them, I'm sure. He was the one for whom St George's Church was built as a memorial, after his death. Les Clark, the son, died here in 1975, but he was, even in retirement, to be again touched by the hand of war.

His only son, John Byron Marcus Clark (Noellie's brother), had enlisted in 1940 for service in WWII. He joined the 2/15 Field Regiment RAA in Malaya. It was then a new regiment, equipped with old 18 pounder guns. By late 1941, the regiment was in Singapore and, after a time, faced the advancing Japanese army. They were re-equipped with the more modern 25 pounders and soon had to fire them for the first time at the enemy. But they were fighting a rear-guard operation as the Japanese army forced the Allies into a withdrawal. John Clark was involved in all of this – he was a bombardier, a two-stripe gunner in action. When the No 1 of his gun crew was killed in action, John stepped in to lead the crew. He was appointed Sergeant in the field, though in a losing battle. Before long our survivors of this fierce fighting had to 'enter the unknown world of the Prisoner of War camps'. John finished up slaving under great duress on the Burma/Thailand railway. His war record says 'cause of death: illness', but as for so many others that meant that he did not survive the brutal treatment, the starvation, the anguish of that infamous regime of the Japanese invasion. His grave is in Thailand in the Kanchamaburi War Cemetery. A huge grief to his father, his sister and the whole Clark family.

But Nellie's contact with war and its effects was not over yet. Sometime after the war finished, she met and married Jim McLean. He had been a WWII soldier serving from 1940. When the war finished he stayed on in the reserves, involved in mopping up operations in Morati and Balikpapan, Borneo (I guess I could perchance have met him there). After that he was posted to Japan with the occupation troops after the Japanese surrender and, among other things, he took a shipload of sheep from Australia to feed the Japanese population, impoverished as it was in defeat.

Truly this was a family that contributed much and suffered much.

Edwin Ernest Channing Hatswell, also known as Ted

Present with us here today is Ted's son Bruce, a resident of Blackheath, who has kindly given us records of his father's WWI experience. Ted Hatswell enlisted in December 1915 and served for the rest of the war with the 7th Light Horse Regiment. He was unmarried at that time and his army pay, as for all private soldiers, was just six shillings a day. The record also shows his address on enlistment as C/- Sefton Hall, Mt Wilson. So today we have another strong connection with the Clark family. Since 1912 he had worked for Henry Marcus Clark, the father of Les, whom we met in the first half of today's talk. After the war Ted married and came back to work at Sefton Hall for a few years before moving to Blackheath.

When I visited Bruce and his brother Ross last week, I was handed a book detailing the whole history of the 7th Light Horse, their father's regiment. It had been written after the end of the war by the commanding officer, Lt Colonel D S Richardson, DSO, with an introduction by Sir Harry Chauvel, KCB, KCMG, Commander of the Desert Mounted Corp in the Middle East. This book was made available only to members of the 7th Light Horse Regiment and I feel very privileged indeed to have read it. It gives a picture of the urgency with which Australia responded to its call for involvement in the Great War; this 7th Light Horse Regiment sprang into existence in November/ December 1914 in very quick time. Men volunteered to enlist because they were ready for adventure and anxious to serve, but, it was noted with regret in this book, their ideas of discipline and the routine of army life were at best vague. The men selected were just put through a riding test over jumps and that was all the riding they got before embarking for Egypt.

Only three weeks before sailing were they issued with rifles and bayonets and they got horses only four days before embarkation. Once at sea the horses were exercised on the ship's decks, which had been covered with ashes and sand, while for the men some rifle exercises and for the officers some sword drill. Once arrived in Cairo, a bit more training and manoeuvres with other units. Then suddenly the Gallipoli campaign got under way and more troops were needed there. So the new 7th Light Horse became involved. Leaving their horses behind, they sailed in a captured German ship right to the Anzac Cove where flashes from the guns could be plainly seen. They landed and occupied a position in support of the Australian Infantry. After the evacuation of the Gallipoli site the 7th Regiment went back to Cairo and from there onwards it took a prominent part in all the important The Light Horse Interchange operations of the Egyptian Theatre of the war. The most famous of these was the Battle of Beersheba, then held by the Turks (allies of Germany).

The entire Allied assault on Beersheba involved thousands of men and horses from England, New Zealand and Australia. Operating under the command of Sir Harry Chauvel were three mounted brigades. But on the last day, the one chosen for the final assault on the ancient town of Beersheba was the 4th Light Horse Brigade, which included the 7th Light Horse Regiment, led by George Macarthur Onslow. One of his soldiers on that day was Ted Hatswell, whose name is on our War Memorial.

Mounted riflemen with bayonets against men in trenches – it didn't make sense but it worked. There were many casualties of men and horses as they charged against the machine gun and rifle fire of an entrenched enemy. Astonished by the speed of the charge and the excitement of the horses, the famous Walers the Australians were riding, the Turkish riflemen forgot to lower the sights on their rifles, which meant that in the close encounter, bullets flew over the heads of our advancing troopers. And once the charge had overcome the entrenched Turks, Beersheba was open to troops of the 4th Brigade. Guns were captured, prisoners taken and before long the horses, many of which had been thirsty for water for the last two days, were able to drink from water quickly pumped up from the wells of Beersheba. One of the troopers said later: 'Well, I've had some good games, but that was the best run I ever had, from start to finish it was just about 6 miles'. But there were good men and horses shot and wounded in the affray.

We're happy to say that Bruce Hatswell's father came through all that without injury, but later, on duty beyond Beersheba, his horse fell and Ted injured his leg and had to go to hospital in Port Said. I understand he walked with a limp for the rest of his life. But he must have been a bit of a lad. His crime sheet - every soldier has a crime sheet - records his having been AWL from hospital for several hours, disobeying hospital orders and drunk while a patient, but he seems to have come home from the war in mid-1919 in pretty good shape after all that.

Just a note about the horses: the Walers were standard Australian stock horses and one British officer said of them: 'Their record in this war places them far above the cavalry horses of any other Nation'. NSW horses were exported to the British Army in India, hence the name Walers. By the end of the war 160,000 Australian horses were sent overseas; only one returned. That was 'Sandy' the horse ridden by the Commander-in-Chief of the AIF, killed at Gallipoli. Sandy was led with an empty saddle at the funeral of his distinguished rider, Sir William Bridges.

2007 Remembrance Day Transcript

- Details

This is a transcript of Arthur Delbridge's 2007 Remembrance Day talk at the Mt Wilson Village Hall, following the service at the War Memorial.

It was in 2001 that our two societies, Progress and Historical, began this series of annual services of remembrance at our war memorial. I believe it was a response to a feeling shared around the Australian community that war and the other faces of terror were necessarily now bulking larger and more urgently in our consciousness than they had for some time past. As a result the national official memorial services in our cities were becoming ever better attended, and the marches more sombre, and overseas the memorial services at Anzac Cove and many other military cemeteries were attracting more and more visitors, with increasing numbers of young Australians making the long journey to them. Possibly also revisitings, especially by old soldiers, to war sites where they had fought and their mates been killed.

The number of new books about the Great War is also a sign of a growing readership, and there are at least two recent books about Australian war memorials that put this small local memorial of ours into a wider context. The first of these books is by a leading Australian historian, K.S. Inglis, with the title Sacred Places and a subtitle War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, first published in 1998 and reprinted five times since then. The other is newer: A Distant Grief: Australians, War Graves and The Great War written by Bart Ziino (2007); a book that concentrates on the fact that the Imperial War Graves Commission in England was given the whole task of burying all dead allied soldiers more or less where they fell, and of raising memorials to the British dead whose bodies were never recovered or identified - the so-called missing. It was not the custom in those days for soldiers' bodies to be brought home for burial and it wasn't until 1993, in response to public urging, that the body of an Australian soldier (buried in a war cemetery on the Somme) was exhumed and returned to Australia and placed in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, to become our own Unknown Australian Soldier. Otherwise we have memorials, not cemeteries.

Today I thought I would speak about two of our local soldiers, who did come back when the war was over. What effects, if any, did their war experience have on the rest of their lives? Perhaps this is, for them (and for us) an unanswerable question. Maybe no visible effect. But I have vivid memories of being taught Latin in high school by a returned soldier, a notable classical scholar who had been gassed in the Great War. He had the most cracked voice, the most awful fits of coughing, the worst temper and the sweetest smile at unexpected moments – he was a post-war wreck physically, a returned soldier who never got over his experience of war.

Fred Mann and George Valder both came back to Mt Wilson. Both of them could have read their own names on our memorial and possibly did. But Professor Inglis, in Sacred Places, stated quite firmly that 'Only in Australia could most men, home from the war, read their own names on its memorials'. Elsewhere, especially in Europe, memorials were exclusively to the dead and the 'missing'. And in Australia at first that seemed to be right and fair. But then a strong movement emerged in favour of listing also the names of returned soldiers. Sir John Monash, who commanded the Australian divisions in France, declared: 'We were all men of one nation—and all volunteers!' That was the key to it. Of course not all volunteers were accepted when they had tried to enlist, for either health or occupation reasons. And volunteering didn't necessarily get you into the front line, where most casualties occur. Behind the front lines are many lines of command and support essential to any engagement. For example, in WWI, 1800 graduates and undergrads of Sydney University went on active service and 197 of these were killed in action. Comparatively a smallish number. But it reflects the fact that a high proportion of those volunteers came from the faculties of medicine and engineering: they were directed to serve where their special skills were needed.

When in the early 1920s Sydney University began to plan its memorial, it was 'for those who have given their lives ... as well as for those who have voluntarily engaged in active military or naval service'. What the universit y finished up with for its memorial was a carillon of 47 bells fitted into its clock tower to be played from a rather special sort of keyboard. I could speak at length about the various ways, from that day to this, that the carillon has kept alive the memorial function it was intended to achieve from its first appearance. It's enough now to say that its biggest bell weighs 4.2 tons, the smallest bell just a few pounds. A carillonist can play on it virtually any tune or theme, and harmonise it into two or three parts, with bells playing simultaneously. Its principal function is memorial. In 1938 I took lessons in playing this great instrument and became a member of the Carillon Family, a small group of appointed players who between them provided carillon music for occasions in the university year, particularly celebrations of national days of the allied countries of World War I.

So there is no limit to the structures that can serve as war memorial, be they hospital, club, park, plaque, pillar or post—or carillon! Inglis says that there are 4000+ war memorials in Australia. Ours is one of the simplest sort, but none the worse for that. Many of them take the form of utilities—a hospital, a community hall, a church, a sports ground that could be undertaken in the expectation of getting a government grant in terms of subsidies and tax concessions for the donors. No such thing happened here. The local impetus was from generous gifts of land and material, plus determined community effort. The crucial gift was of a piece of land cut off from the Dennarque estate, given for just this purpose by Flora Mann, the mother of the Fred Mann whose name is, with 26 others, engraved on our memorial: Frederick Farrell Mann (1894-1962).

The research on Fred Mann's life is well covered in Mary Reynolds's excellent article contained in Newsletter No. 12 of the Mt Wilson and Mt Irvine Historical Society (July 2005). The Society has a large and growing archive, all expertly catalogued, with photographs, letters, official documents and news items housed in the Study Centre and accessible through the Society's personnel, as many of you know from when you sought information on the history of your land titles. Mary is our only professional historian and a very approachable source of historical information on our two villages.

In 1894 the Mann family bought Dennarque from its original owners, the Merewethers, and in that same year Fred was born, the youngest son of James and Flora Mann. He was educated at Riverview in Sydney and in 1915, not so long after schooling was over and work had begun, he and his brother Alfred sailed to London on the Orontes and enlisted—Fred in the Royal Field Artillery, Alfred in the Royal Navy Air Service. Fred's older brother James Furneaux also enlisted. Fred served with his regiment in Salonika (a seaport area in the Baltic Peninsula), and also in Egypt and Northern Italy. It is difficult to get detailed information on his service history from British sources, but he survived. Sadly though, his brother Alfred was killed on 19 November, in France. This death in the family was undoubtedly a heartfelt motive with Flora for her donation of a portion of Dennarque land as the site for the war memorial—our war memorial.

Flora died in 1921, and Fred was by then a man of means: he bought Yengo when it came on the market in 1923. He developed both house and garden, changing its name from Yengo to Stone Lodge. He turned the stables into a workshop, called Cherry Tree Cottage, and here he developed his name as a potter of some note. He became a much loved member of the community, with music, and parties always enjoyed by the local children. He once made quite a social splash around the village by inviting the touring Russian Ballet to stay at Stone Lodge.

But he was not yet quite finished with war. He rejoined for WWII as a lieutenant, working first with the Red Cross, at Ingleburn, then on a hospital ship, and fund-raising in support of the Free French. Then in 1944 he was sent to England 'to organise the furnishing of houses for Australian prisoners of war on their return to Britain'. Back in Mt Wilson he contributed generously to funding for the construction of this very place, the Village Hall.

He left Mt Wilson in the early fifties for Sydney where at length he fell ill and died, aged 69. John Valder perhaps summed him up, saying: 'He was a lovely, warm, generous, cheerful, friendly man', and we can be grateful that he, this way, fulfilled the agreeable and worthy life of a returned soldier.

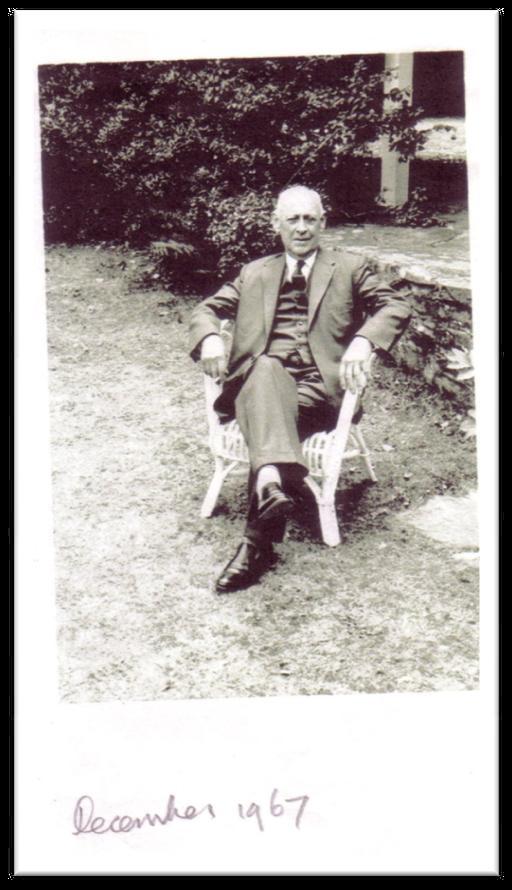

Let us now follow the fortunes of another returned soldier who, with his wife Isa, established Nooroo. He was born in Wagga Wagga in 1896 and spent his early years there. His father, also George, had come to Australia from his native England in about 1880. Two things about him for this story are that he became the Principal of the Hawkesbury Agricultural College and in 1902 he bought and developed a piece of land in Mt Wilson.

When he was not quite 20, George (the son) enlisted for overseas service in the army. After initial training as an army driver he was transferred to an Australian field artillery brigade as a driver. Within months from enlistment he sailed on the Orontes and did further training and service as a driver in the 6th Army Brigade, no doubt as a driver carrying supplies and ammunition to wherever they were needed. Dangerous work indeed! He was there, doing that, until the end of the war, but he had to wait until July 1919 for transport home. He spent the waiting time, as many soldiers did, furthering their education with special studies. He arrived back in Sydney for discharge in good health and he took a sulky and drove it to Mt Wilson and lived here for the rest of his life.

He bought land in Church Lane and established Nooroo as an apple and pear orchard. He married Isa and they had Peter and John, both of whom were destined to have remarkable careers well away from Mt Wilson (though with a heartfelt connection to it, to this day!). Both boys started their school education in the one-teacher Mt Wilson Public School, then moved on to Shore, as boarders—clearly straining the parent's financial resources). Their father, our George, abandoned the orchard enterprise, and changed it into a flower-growing venture, with the flowers taken to Sydney for selling to florists. Later, urged on and assisted by son Peter (by then a well-known botanist), it was turned into a viewing garden, which is as we see it today, and as it appeared, famously, on an Australian postage stamp in 1989.

Meanwhile Peter became famous as botanist, university lecturer, broadcaster, universal plant collector and author. He was awarded an Order of Australia for his contributions to botany and horticulture, and is still much sought after as a witty and informative public speaker.

His brother John first became a Sydney journalist then a man of business whose catch words were 'enterprise, incentive, reward'. He became a stock broker, and for three years the chairman of the Stock Exchange. Although he had no wish to become a politician, in 1982 he became president of the NSW Liberal Party—a truly liberal Liberal, not a conservative. His words: 'I'm essentially a simple person. My whole career has been a constant surprise to me.' Both men are great supporters of our Historical Society.

Well, for George, the father of all this, post-war life was pretty hard, but he had huge support from Isa, his wife, and his sons Peter and John. He died here in Mt Wilson, but Isa carried on with all the work of the property and its place in Mt Wilson life, until she reached the age of 90, when she removed to Sydney. In 1993 a village function was arranged to pay tribute to the outstanding contribution made by George Valder and his family to the community life and spirit of Mt Wilson.

George Valder

2005 Remembrance Day Transcript

- Details

This is a transcript of Arthur Delbridge's 2005 Remembrance Day talk at the Mt Wilson Village Hall, following the service at the War Memorial.

You will have noticed that our Soldiers Memorial shows the names of 36 soldiers who served in three wars: the so-called Great War of 1914-1918; World War II of 1939-1945; and the Vietnam War. Against four of the names there is a star indicating that those four soldiers were killed while serving. There are many ways a soldier can lose his life in war and chance often plays a big part. You might remember the story of Viv Kirk told at last year’s Remembrance Service. He came back to civilian life with a bullet still lodged so close to his heart that no surgeon dared to remove it, and he lived the rest of his life with it embedded there. A bullet wound is perhaps the archetypal cause of a military death, but the chance element is always present. A bullet is aimed and it hits the target or it misses while shells, bombs, land mines and gas are more indiscriminate. But there are other threats to the soldier’s life. Just the strain on his body and mind can lead to serious illness and even death – by disease (malaria, for example, which killed so many soldiers in New Guinea), while a prisoner of war, while attempting to escape the prison camp, by mistreatment and starvation (as happened to so many soldiers on the Burma railway), in combat for those not sufficiently trained or experienced or otherwise unfit for it, or by accident. As Donald Rumsfelt so brutally said in an interview about American war dead in Iraq: ‘Stuff happens’!

Today let us look at the life of two soldiers, one who died while serving and one who survived. Perhaps it is not more meritorious in war either to die or to survive. It’s the costs that are different. So we remember all who served, as our own memorial puts it. Remember also all those in our community now who served but whose names are not on the memorial.

Noel Henry Knight-Brown

Noel Henry Knight-Brown

His father, the late Basil Knight-Brown, was one of the group of three young men who first took up a selection at Mt Irvine in 1897. There have been three generations of the family living there until very recently. I am grateful to Julia Reynolds, daughter of Bill Knight-Brown, for sending me copies of letters and newspaper cuttings and a full record of service of her uncle, whom she had never in life known.

Noel enlisted in the Air Force in January 1941 at the age of 23. After a short initial training period he was sent to a service flying training school for 3 months, then on to England and eventually to a Bomber and Gunnery Flight at an airfield in Binbrook in September. By early 1943 he had reached the rank of Flying Officer. When he was presented with his ‘wings’, the presentation was filmed as part of a motion picture called ‘Captain of the Clouds’ filmed as part of a motion picture called ‘Captain of the Clouds’ subsequently screened in the UK and in Australia. A photograph of him in the uniform shows a handsome, elegant young fellow. He had recently married an English lady, Rita Barrie, who at the time was serving in the WAAF’s, also since 1941. Letters he sent back home show that all this traveling, all this training, all this exciting military experience, this success and advancement of his flying career gave him great pleasure. In his whole time awayhe wrote weekly letters and sometimes telegrams to his family in Australia, and especially to his mother at ‘Painui’, Mt Irvine. There is a very large file of these letters in our Historical Society archives, kindly donated by Julia Reynolds.

Now his record of service also gives details of the flight which took off from his station at Binbrook to ‘report on weather conditions’ at an air firing range just 21 miles away’. Noel Knight-Brown was not the pilot on this flight, but presumably an observer. The plane flew off on this mission but it just never returned. At this point his Service Record says: ‘deceased 26/10/43 (officially presumed lost at sea off the coast of the United Kingdom’. His wife, by then stationed in Scotland, received a letter telling her that he was missing. At the same time his mother received a telegram, and we have this very document on file, which said rather baldly ‘Regret to inform you that your son Flying Officer Noel Knight-Brown is missing as a result of a non-operational flight on 26th October 1943. STOP Letter will follow. Signed Air Force, South Yarra, Melbourne’. A letter did follow, a deeply personal one written by his Squadron Leader in England, no doubt written at night, as such letters often were, after a hard day’s service duties.

You may rest assured that as soon as anything is known definitely you will be informed. Flying Officer Knight-Brown had been with the Unit only a month, and had already

become very popular. He was always ready, willing, and anxious to tackle any job whatever it might be, and he was undoubtedly one of the best pilots in this Unit.

Signed yours sincerely,

Lewis Murphy

Squadron-Leader, Commanding,

1481Flight, Binbrook.

But there was no further news, no definite account of what had happened to comfort the family if only with certain knowledge and a sense of what these days we call ‘closure’. Only one line in the report says: ‘Although such a flight would not necessitate flying out to sea, a wing was picked up at sea by a trawler, and identified as the wing of the missing aircraft’.

Missing! Of all the ways to die, this is perhaps the worst for the relatives because of the unanswered questions of How did it happen? Where is he? Why?

Richard Owen Wynne

Richard Owen Wynne

For this story I begin by reading extracts from the frontispiece article from The Wasp, the journal of the 16th Foot, a battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment Complex in England. This issue of The Wasp is Volume 2, Number 5, April 1925 and a copy of it was kindly sent to me by Irene Wynne. Irene is married to Mike Wynne, Richard’s grandson. This article gives an account of Richard Wynne’s early life in England and his experiences in the British Army throughout the Great War.

Lieut-Col Richard Owen Wynne was born at Moss Vale, NSW, on 12 June 1892. He was grandson of the Richard Wynne who in 1875 bought land in Mt Wilson that has been the site of the Wynne family residences ever since. He left Australia in 1902 and was educated at Marlborough College and at the outbreak of war was at Clare College, Cambridge. At Marlborough he played on several occasions in the school Rugby fifteen. He was a member of the school shooting eight, firing with the team for the Ashburton Shield at Bisley for four years from 1907 to 1910. At Cambridge he rowed for two years in the Clare College First Lent and May Boats in 1913 and 1914.

At the outbreak of war he joined the 3rd Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment and went out to France early in 1915. He then transferred to the 2nd Battalion in June 1915 in which he served until May 1918, all this time in France. He was then given command of the 18th King’ s Liverpool Regiment in August 1918 and continued in this role until the Battalion went home and disbanded in May 1919.

Col. Wynne was awarded the DSO in July 1916 and a bar to the DSO in June 1918 and was four times mentioned in dispatches. He was wounded in October 1918 but remained at duty. The actions for which he was awarded his DSO and bar perhaps best describe his able leadership in action and his complete disregard for his own personal safety, but they cannot portray his charming character and his modesty.

He was given the DSO for:

…his splendid work on July 31st, 1916, when he laid out and superintended the consolidation of 300 yards of new trench along the line of the Maltzhorn Ridge, under heavy shell and machine gun fire. This was a most important piece of new trench, and he showed wonderful coolness and quickness in getting to work, which helped greatly the consolidation of our line along this ridge. In addition, at Trones Wood, on July 11th and 12th, 1916 he was mainly responsible for the establishment of a footing and the consolidation of the south-west corner of the Wood, which was carried out under continuous shell and rifle fire.

The bar to his DSO was awarded for:

…his conspicuous gallantry and leadership in action between March 21st and 28th, 1918, and especially for his action on March 27th, at La Folies, when parties of Germans succeeded in working some machine guns close up to the front line held by the Battalion. Observing this, Wynne personally led an attack against the machine guns, and succeeded in driving them off, and himself killed the Officer commanding the Germans. At all times Col. Wynne commanded his men with great skill and bravery, and showed complete disregard for his own safety.

“Reggie” Wynne was obviously cut out for a soldier, and it was with great regret that we heard that he could not go on soldiering, but would have to return to look after his estates in Australia. So he returned to the land of his birth and is now living in the Blue Mountains, NSW.

That’s the end of the Wasp’s account of Col. Wynne’s service in the Great War. He returned to Mt Wilson, but before long went back to England (that was in 1921), and in a church in Kensington he married Florence Mariamne Ronald. Then back again to Mt Wilson and began building the present house that we know as Wynstay. There they raised three children, Jan, Mervyn and Ron. Their grand-daughter, Wendy Smart, lives there now.

Richard Owen Wynne’s life after the war displays a continuing military involvement against a background of village life in Mt Wilson. We know, for example, that he took a leading role in the local rifle club. Indeed our neighbour, John Holt, as a lad, was a member of the same club, and remembers Richard Wynne from that time. For eight years Col. Wynne held the post of Aide-decamp to Lord Wakehurst, Governor of NSW from 1937 to 1945, a period which spans World War II. This was a very responsible role in state affairs and naturally brought him into touch with many notable people. The Historical Society has a note from Pam Lovell, daughter of Sir William Owen, (High Court Judge), recalling that every year her father, together with Sir John Medley and Lord Wakehurst, went trout fishing with Richard Wynne, on the upper Murrumbidgee River. But it was not all such easy living: I have here a letter written by Lord Wakehurst as he was returning to England after his term as Governor. It reads (in part):

My dear Owen, I feel I cannot leave NSW without expressing my very deep gratitude for your loyal and devoted service, during the eight years of my term of office. I should like you to realise how much it has meant to my wife and to myself to know that we could always rely on your help. There have been times, especially during the war years, when difficulties and inconveniences have been numerous, but you have always accepted them cheerfully, and have always risen to the occasion.

In village life here in Mt Wilson both the Col. and his wife Mariamne were very active. He called himself ‘a worker among workers’. He took a leading hand in setting up the Village Hall Trust and its Committee. He was the prime mover in the decision to give the Community Hall over into the care and ownership of the Blue Mountains City Council. He donated many tracts of land to the village, including those for the Church, the Post House and Founders Corner. Col. Wynne died in 1967, and is buried, with his wife Mariamne, in the graveyard of our St George’s Church.