This is a transcript of Arthur Delbridge's 2007 Remembrance Day talk at the Mt Wilson Village Hall, following the service at the War Memorial.

It was in 2001 that our two societies, Progress and Historical, began this series of annual services of remembrance at our war memorial. I believe it was a response to a feeling shared around the Australian community that war and the other faces of terror were necessarily now bulking larger and more urgently in our consciousness than they had for some time past. As a result the national official memorial services in our cities were becoming ever better attended, and the marches more sombre, and overseas the memorial services at Anzac Cove and many other military cemeteries were attracting more and more visitors, with increasing numbers of young Australians making the long journey to them. Possibly also revisitings, especially by old soldiers, to war sites where they had fought and their mates been killed.

The number of new books about the Great War is also a sign of a growing readership, and there are at least two recent books about Australian war memorials that put this small local memorial of ours into a wider context. The first of these books is by a leading Australian historian, K.S. Inglis, with the title Sacred Places and a subtitle War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, first published in 1998 and reprinted five times since then. The other is newer: A Distant Grief: Australians, War Graves and The Great War written by Bart Ziino (2007); a book that concentrates on the fact that the Imperial War Graves Commission in England was given the whole task of burying all dead allied soldiers more or less where they fell, and of raising memorials to the British dead whose bodies were never recovered or identified - the so-called missing. It was not the custom in those days for soldiers' bodies to be brought home for burial and it wasn't until 1993, in response to public urging, that the body of an Australian soldier (buried in a war cemetery on the Somme) was exhumed and returned to Australia and placed in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, to become our own Unknown Australian Soldier. Otherwise we have memorials, not cemeteries.

Today I thought I would speak about two of our local soldiers, who did come back when the war was over. What effects, if any, did their war experience have on the rest of their lives? Perhaps this is, for them (and for us) an unanswerable question. Maybe no visible effect. But I have vivid memories of being taught Latin in high school by a returned soldier, a notable classical scholar who had been gassed in the Great War. He had the most cracked voice, the most awful fits of coughing, the worst temper and the sweetest smile at unexpected moments – he was a post-war wreck physically, a returned soldier who never got over his experience of war.

Fred Mann and George Valder both came back to Mt Wilson. Both of them could have read their own names on our memorial and possibly did. But Professor Inglis, in Sacred Places, stated quite firmly that 'Only in Australia could most men, home from the war, read their own names on its memorials'. Elsewhere, especially in Europe, memorials were exclusively to the dead and the 'missing'. And in Australia at first that seemed to be right and fair. But then a strong movement emerged in favour of listing also the names of returned soldiers. Sir John Monash, who commanded the Australian divisions in France, declared: 'We were all men of one nation—and all volunteers!' That was the key to it. Of course not all volunteers were accepted when they had tried to enlist, for either health or occupation reasons. And volunteering didn't necessarily get you into the front line, where most casualties occur. Behind the front lines are many lines of command and support essential to any engagement. For example, in WWI, 1800 graduates and undergrads of Sydney University went on active service and 197 of these were killed in action. Comparatively a smallish number. But it reflects the fact that a high proportion of those volunteers came from the faculties of medicine and engineering: they were directed to serve where their special skills were needed.

When in the early 1920s Sydney University began to plan its memorial, it was 'for those who have given their lives ... as well as for those who have voluntarily engaged in active military or naval service'. What the universit y finished up with for its memorial was a carillon of 47 bells fitted into its clock tower to be played from a rather special sort of keyboard. I could speak at length about the various ways, from that day to this, that the carillon has kept alive the memorial function it was intended to achieve from its first appearance. It's enough now to say that its biggest bell weighs 4.2 tons, the smallest bell just a few pounds. A carillonist can play on it virtually any tune or theme, and harmonise it into two or three parts, with bells playing simultaneously. Its principal function is memorial. In 1938 I took lessons in playing this great instrument and became a member of the Carillon Family, a small group of appointed players who between them provided carillon music for occasions in the university year, particularly celebrations of national days of the allied countries of World War I.

So there is no limit to the structures that can serve as war memorial, be they hospital, club, park, plaque, pillar or post—or carillon! Inglis says that there are 4000+ war memorials in Australia. Ours is one of the simplest sort, but none the worse for that. Many of them take the form of utilities—a hospital, a community hall, a church, a sports ground that could be undertaken in the expectation of getting a government grant in terms of subsidies and tax concessions for the donors. No such thing happened here. The local impetus was from generous gifts of land and material, plus determined community effort. The crucial gift was of a piece of land cut off from the Dennarque estate, given for just this purpose by Flora Mann, the mother of the Fred Mann whose name is, with 26 others, engraved on our memorial: Frederick Farrell Mann (1894-1962).

The research on Fred Mann's life is well covered in Mary Reynolds's excellent article contained in Newsletter No. 12 of the Mt Wilson and Mt Irvine Historical Society (July 2005). The Society has a large and growing archive, all expertly catalogued, with photographs, letters, official documents and news items housed in the Study Centre and accessible through the Society's personnel, as many of you know from when you sought information on the history of your land titles. Mary is our only professional historian and a very approachable source of historical information on our two villages.

In 1894 the Mann family bought Dennarque from its original owners, the Merewethers, and in that same year Fred was born, the youngest son of James and Flora Mann. He was educated at Riverview in Sydney and in 1915, not so long after schooling was over and work had begun, he and his brother Alfred sailed to London on the Orontes and enlisted—Fred in the Royal Field Artillery, Alfred in the Royal Navy Air Service. Fred's older brother James Furneaux also enlisted. Fred served with his regiment in Salonika (a seaport area in the Baltic Peninsula), and also in Egypt and Northern Italy. It is difficult to get detailed information on his service history from British sources, but he survived. Sadly though, his brother Alfred was killed on 19 November, in France. This death in the family was undoubtedly a heartfelt motive with Flora for her donation of a portion of Dennarque land as the site for the war memorial—our war memorial.

Flora died in 1921, and Fred was by then a man of means: he bought Yengo when it came on the market in 1923. He developed both house and garden, changing its name from Yengo to Stone Lodge. He turned the stables into a workshop, called Cherry Tree Cottage, and here he developed his name as a potter of some note. He became a much loved member of the community, with music, and parties always enjoyed by the local children. He once made quite a social splash around the village by inviting the touring Russian Ballet to stay at Stone Lodge.

But he was not yet quite finished with war. He rejoined for WWII as a lieutenant, working first with the Red Cross, at Ingleburn, then on a hospital ship, and fund-raising in support of the Free French. Then in 1944 he was sent to England 'to organise the furnishing of houses for Australian prisoners of war on their return to Britain'. Back in Mt Wilson he contributed generously to funding for the construction of this very place, the Village Hall.

He left Mt Wilson in the early fifties for Sydney where at length he fell ill and died, aged 69. John Valder perhaps summed him up, saying: 'He was a lovely, warm, generous, cheerful, friendly man', and we can be grateful that he, this way, fulfilled the agreeable and worthy life of a returned soldier.

Let us now follow the fortunes of another returned soldier who, with his wife Isa, established Nooroo. He was born in Wagga Wagga in 1896 and spent his early years there. His father, also George, had come to Australia from his native England in about 1880. Two things about him for this story are that he became the Principal of the Hawkesbury Agricultural College and in 1902 he bought and developed a piece of land in Mt Wilson.

When he was not quite 20, George (the son) enlisted for overseas service in the army. After initial training as an army driver he was transferred to an Australian field artillery brigade as a driver. Within months from enlistment he sailed on the Orontes and did further training and service as a driver in the 6th Army Brigade, no doubt as a driver carrying supplies and ammunition to wherever they were needed. Dangerous work indeed! He was there, doing that, until the end of the war, but he had to wait until July 1919 for transport home. He spent the waiting time, as many soldiers did, furthering their education with special studies. He arrived back in Sydney for discharge in good health and he took a sulky and drove it to Mt Wilson and lived here for the rest of his life.

He bought land in Church Lane and established Nooroo as an apple and pear orchard. He married Isa and they had Peter and John, both of whom were destined to have remarkable careers well away from Mt Wilson (though with a heartfelt connection to it, to this day!). Both boys started their school education in the one-teacher Mt Wilson Public School, then moved on to Shore, as boarders—clearly straining the parent's financial resources). Their father, our George, abandoned the orchard enterprise, and changed it into a flower-growing venture, with the flowers taken to Sydney for selling to florists. Later, urged on and assisted by son Peter (by then a well-known botanist), it was turned into a viewing garden, which is as we see it today, and as it appeared, famously, on an Australian postage stamp in 1989.

Meanwhile Peter became famous as botanist, university lecturer, broadcaster, universal plant collector and author. He was awarded an Order of Australia for his contributions to botany and horticulture, and is still much sought after as a witty and informative public speaker.

His brother John first became a Sydney journalist then a man of business whose catch words were 'enterprise, incentive, reward'. He became a stock broker, and for three years the chairman of the Stock Exchange. Although he had no wish to become a politician, in 1982 he became president of the NSW Liberal Party—a truly liberal Liberal, not a conservative. His words: 'I'm essentially a simple person. My whole career has been a constant surprise to me.' Both men are great supporters of our Historical Society.

Well, for George, the father of all this, post-war life was pretty hard, but he had huge support from Isa, his wife, and his sons Peter and John. He died here in Mt Wilson, but Isa carried on with all the work of the property and its place in Mt Wilson life, until she reached the age of 90, when she removed to Sydney. In 1993 a village function was arranged to pay tribute to the outstanding contribution made by George Valder and his family to the community life and spirit of Mt Wilson.

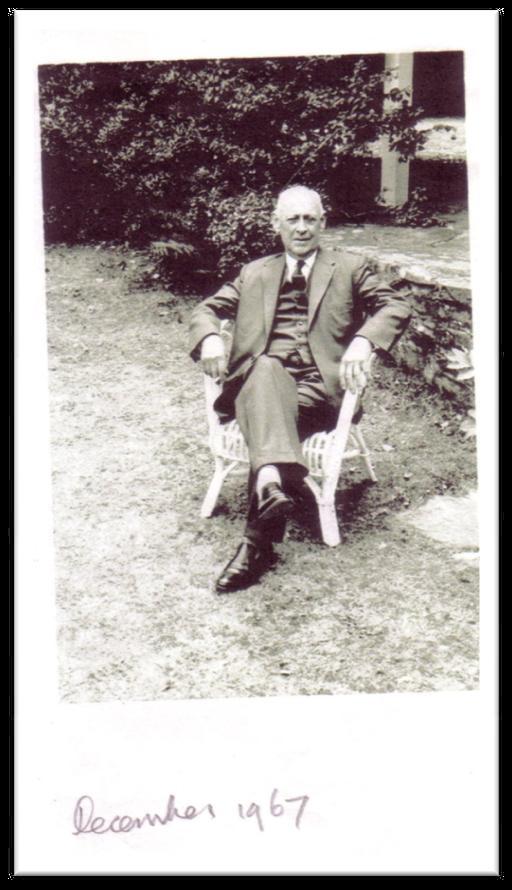

George Valder